Halakha as Communal Practice: Launching the Teshuva-Writing Collective

by Rabbi Becky Silverstein and Laynie Soloman, co-Directors of the Trans Halakha Project

Halakha is all about questions: What’s the blessing to be said in response to this particular experience? What counts as “taste”? When does evening truly begin? And ultimately, how can I express myself authentically through sacred Jewish language? Asking questions and developing responses is one of the most expansive genres of written halakha, known as she’elot u’teshuvot (“questions” and “responses”), or the acronym shu’tim. Throughout history, the process of asking and responding to questions has taken different forms, from early rabbinic disciple-circles, to the establishment of rabbinic courts, to questioners sending questions in the form of pen-pal letters to their rabbis, to the development of law committees like the Conservative Movement’s Committee on Jewish Law & Standards. Each of these iterations—both in the ways they are configured, be it democratic committees or through direct relationships and in the questions and answers they address—reflects a particular historical, cultural, or communal set of values.

It’s time for these questions and responses to reflect us.

This desire to feel ourselves reflected in the dynamic process of questioning and responding in halakhic language is not simply a desire for our own representation (which would still be a holy endeavor!). It is a yearning to restore halakha to its representative roots.

Our learning is grounded, in part, by the work of Robert Cover, an American legal theorist, who drew on frameworks from halakha to shape his approach to law as a creative world-building project. In a famous essay, “Nomos and Narrative,” Cover writes:

No set of legal institutions or prescriptions exists apart from the narratives that locate it and give it meaning. For every constitution there is an epic, for each decalogue a scripture.

Once understood in the context of the narratives that give it meaning, law becomes not merely a system of rules to be observed, but a world in which we live. In this normative world, law and narrative are inseparably related. Every prescription is insistent in its demand to be located in discourse – to be supplied with history and destiny, beginning and end, explanation and purpose. And every narrative is insistent in its demand for its prescriptive point, its moral.

Cover argues that law is shaped by the communities that give its normative structures and practices definition; all laws are situated within a discourse, the “narratives” that give them meaning. This discourse is created by the community itself—what stories we tell about a practice, our memories of it, what associations we have as individuals or collectives with the practices themselves. All of that is, according to Robert Cover, constantly shaping the law–or, in our case, halakha—and in turn, is an essential part of halakha.

We, guided by Cover, understand that halakha is fundamentally shaped by stories and commitments—be they spiritual, political, or ideological—and the lived realities we hold. These are all the narratives that give halakha meaning. Many of us have been taught to see halakha as a path that preferences objectivity, behavioral regulation, and external authority. As trans and non-binary people, we have been viewed as the objects of this path, “issues” to address, and “halakhic problems” to solve. Through our learning and teaching at SVARA, we seek to uncover principles that help us see ourselves—and all SVARA-niks—as players in the world of the Talmud and actors in halakhic discourse.

One of these principles, which is guiding our work in the Trans Halakha Project, comes to us in a story from the gemara in Bava Batra 130b, in which Rava, a leading Babylonian sage, speaks to his assembled students:

אֲמַר לְהוּ רָבָא לְרַב פָּפָּא וּלְרַב הוּנָא בְּרֵיהּ דְּרַב יְהוֹשֻׁעַ כִּי אָתֵי פִּסְקָא דְּדִינָא דִּידִי לְקַמַּיְיכוּ וְחָזֵיתוּ בֵּיהּ פִּירְכָא לָא תִּקְרְעוּהוּ עַד דְּאָתֵיתוּ לְקַמַּאי אִי אִית לִי טַעְמָא אָמֵינָא לְכוּ וְאִי לָא הָדַרְנָא בִּי

לְאַחַר מִיתָה לָא מִיקְרָע תִּקְרְעוּהוּ וּמִגְמָר נָמֵי לָא תִּגְמְרוּ מִינֵּיהּ לָא מִיקְרָע תִּקְרְעוּנֵיהּ דְּאִי הֲוַאי הָתָם דִּלְמָא הֲוָה אָמֵינָא לְכוּ טַעְמָא מִגְמָר נָמֵי לָא תִּגְמְרוּ מִינֵּיהּ דְּאֵין לַדַּיָּין אֶלָּא מַה שֶּׁעֵינָיו רוֹאוֹת

Rava said to [his students] Rav Pappa and to Rav Huna the son of Rav Yehoshua: When a psak of mine comes before you and you see a challenge within it [i.e. a reason to refute it], do not tear it up until you come before me. If I have a reason [for the ruling], I will share that with you, and if I do not, I will retract my ruling.

After I die [if such a case should occur], do not tear it up, but do not learn from it. Do not tear it up, for had I been there perhaps I could have told you a reason [for the ruling]. Do not learn from it either, for a judge has only what their eyes see.1

Rava tells his students not to rely on his rulings once he has died—they, as judges, should rule only based on what they see, only based on what’s in front of them. This phrase appears throughout the Talmud and halakhic literature as an injunction against ruling exclusively on precedent rather than fully evaluating a case as it exists before a judge’s eyes. Lest we assume this text is about physical sight, Jastrow is here to remind us that the root for “see” is ראי, which means “to perceive,” “to recognize,” and “to understand.” The Rashbam (11-12th century French Tosafist) adds to this understanding, and suggests that this phrase refers not only to material data in a case but “matters of judgment based on logical reasoning (svara)…in which the judge must be guided by the dictates of his mind (mah she-libbo ro’ehu)”. (1) This interpretation expands the Talmudic phrase to include the emotional, moral realities of both the judge and the case itself. This principle, “a judge has only what his eyes see,” captures the need to contextualize psak, halakhic decision-making, within a specific story, experience, or set of lived and felt data.

So, what does this principle teach us about creating and shaping halakha? A judge, i.e., a player in the halakhic system, must see—understand, be able to perceive—all of the dimensions of the context of a case when they offer a ruling. They must know the ins-and-outs, fully understand the context, be attuned to the implications, know the full reality behind the case itself, and understand the narratives that give any subjective ruling a meaningful outcome.This is a radical force within halakha that honors context, specificity, story, and relationship as central to law-making.

For centuries, dayanim, judges, have not seen us. So often, Jewish communities are asking questions about trans people and trans bodies, and our cisgender comrades fail to fully “see” us, to share our assumptions, to acknowledge our dynamic and powerful experiences, to learn from the ways we inhabit our bodies. In this frame, judges cannot offer rulings about that which they cannot understand, places in which their ‘svara’ is not attuned.

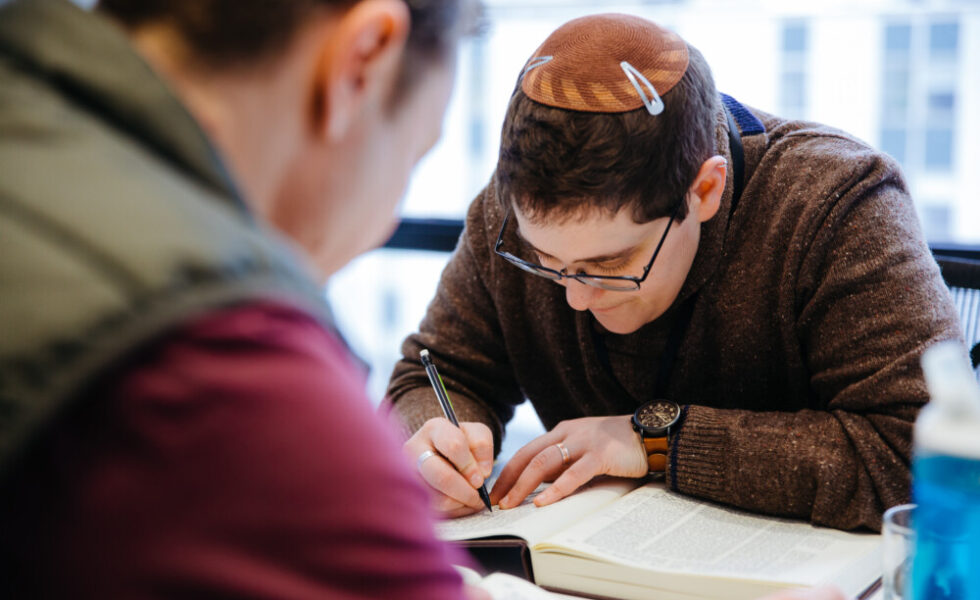

This week, the Trans Halakha Project is excited to open applications for the Teshuva-Writing Collective, a team of 10-12 trans Jews who participate in the centuries-long process of creating halakha by authoring teshuvot that respond to questions about Jewish life and practice that emerge directly from trans people. We see the Trans Halakha Project as a world-building opportunity which uses halakhic literature and language to empower trans Jews to become judges. This work depends on acknowledging the power of that which only our perception can reveal and uplifting the dayanim, judges, whose experiences are not yet at the center of halakhic exploration.

May this work support our communities—and all of us—to, in the language of the Rashbam, expand that which our hearts see, so that we may all benefit from the lived realities, stories, and narratives of trans folks in and through halakha.

*With gratitude to SVARA-nik Russell Pearce, with whom Laynie has been exploring lots this Torah, Robert Cover, and legal theory. Much of the sharpening and deepening of these ideas have been formed in chevruta with Russ.

(1) Rashbam commentary to Bava Batra 131a; translation from Joel Roth, The Halakhic Process: A Systemic Analysis, p. 84.

Applications for the Teshuva-Writing Collective can be found here and are due May 1, 2022. Questions? Write to Laynie (laynie@svara.org). Want to stay up-to-date on the Trans Halakha Project? Sign up for our mailing list here.

SVARA: A Traditionally Radical Yeshiva

SVARA: A Traditionally Radical Yeshiva